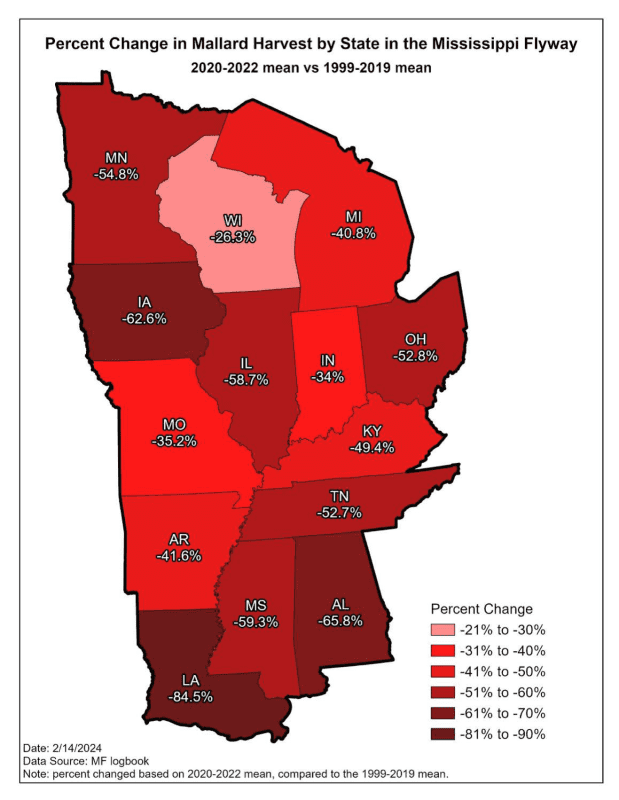

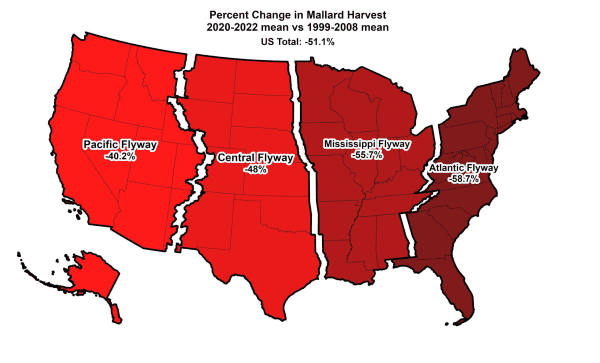

I don’t know of any waterfowler that wouldn’t be ecstatic coming out of the marsh or field with a strap of greenhead mallards over their back. In years past, that was the gold standard. But in the last couple of decades, it’s become increasingly harder and harder to do. And the decline is not restricted to one flyway or another. Uniformly, mallard numbers have been down across the country. The percent change in mallard harvest between the 2020-2022 mean versus the 1999-2008 mean has been -40.2 % in the Pacific Flyway, -48% in the Central Flyway, -55.7% in the Mississippi Flyway, and a stunning -58.7% in the Atlantic Flyway. Overall, harvest declined 51.1% across the country when comparing those two time periods.

The reasons are not concise or uniform. Persistent drought has had a massive impact on the Mid-Continent mallard population, and mallards have not recovered to pre-drought levels there. Genetics are being pointed to as a major factor in the downturn in mallard numbers in the Atlantic Flyway and Great Lakes Region. Researchers are discovering that game farm mallards have polluted the gene pool of wild mallards and are now producing a less viable product. Researchers have discovered as many as 56% of the wild mallard populations in the northern Mississippi flyway have domestic genes in their lineage. In the Atlantic flyway, that percentage may be closer to 100%. The result is an inferior product that doesn’t survive or do well in the wild.

“The mid-continent mallard population is closely tied to the health of the prairie pothole region,” shared Dr. John M. Coluccy, Director of Conservation & Planning Great Lakes/Atlantic Region with Ducks Unlimited. “The Great Lakes Region is not as affected by drought.”

Mallard numbers peaked at 12 million birds in 2016 in the Mid-Continent region but have plummeted to 6 million mallards since then. The historic drought of 2021-2022 devastated duck numbers, and mallards in particular, in the central part of the country, and conditions have not rebounded yet. “The prairies are not looking much better,” stated Dr. Coluccy. “The poor habitat conditions will affect all species. It’s still early, but the outlook doesn’t look too rosy.”

“What we saw was a perfect storm that had led to the mallard decline in the Mid-Continent population,” offered Dr. Coluccy.

Understanding why the mallard decline in the Great Lakes Region and Atlantic Flyway is complicated. “We’re trying to put our fingers on it,” said Coluccy. An ongoing study in the Atlantic Flyway that will fit 1,200-plus radio transmitters on hen mallards across the flyway during the winter hoped to shed light on the issue. These state-of-the-art solar-charged tracking devices will allow researchers to learn about habitat use and behavior throughout the entire year.

Historically, mallards were never common in the Atlantic Flyway. Depletion of wild stocks promoted efforts to raise and release mallards in the early 1900s to augment wild populations. Continued private releases through the present day have polluted the gene pool to the point where very few wild mallards are left in the flyway. Ironically, the mallard population in southeast Canada has been fairly stable while that in the northeast US has declined.

“The good news is that we still have pure wild mallards, and in time, natural selection should weed out maladaptive genes associated with game-farm mallards. If game-farm mallard genes adversely impact survival or reproduction, then we would expect to see those traits lost through time,” said Colucci. “Wild mallards are resilient, but continued captive releases will provide a constant source of these genes.”

Habitat is another story. “We are constantly losing wetlands,” said Coluccy. The CRP boom boosted duck populations, and now that we’re losing CRP and wetland habitat combined with some less-than-ideal conditions on the habitat that remains, duck populations, particularly Mid-Continent mallard populations, are suffering.

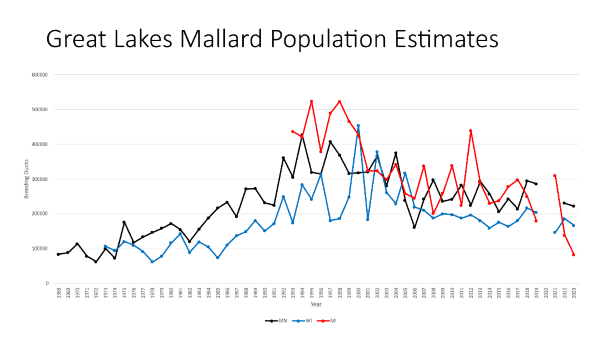

Nowhere is the mallard decline more pronounced in Mid-Continent mallards than in the Great Lakes Region. Whereas the decline in the Mid-Continent population is alarming, it’s thought to be reversible with better nesting conditions and more quality habitat in the prairie pothole region. The same may not be true in the Great Lake Region, including Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan.

The mallard population in the GLR has declined from 1.2 million birds a couple of decades ago to 480,295. Researchers estimate that in the 1990s, there were over a million mallards in the Great Lake Region. Some researchers hypothesize that the decline is due to massive releases of game farm mallards in the 1920s. An estimate from 2001 suggests well over 300,000 game-farm mallards were released on licensed shooting preserves, with the majority released in the Atlantic (79%) and Mississippi (18%) Flyway. Long-term continued releases have resulted in hybridization with wild mallards, ultimately polluting the mallard gene pool.

“There are huge differences between wild versus game-farm mallards,” offered Ben Luukkonen, who has been researching mallards as a PhD student at Michigan State University’s Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. “One major difference is that wild x game-farm mallard hybrids tend to use urban areas and are less likely to migrate. They feed at parks, are subjected to relatively mild winters, and are not subjected to the risks and perils of migration. Consequently, their survival rates are quite high, especially for drakes. Wild mallards exhibit higher mortality due to migration, hunting, predation, and starvation risks. That alone puts the odds in favor of the game-farm mallards.”

But game-farm mallards don’t have the same nesting instincts as wild mallards. The sites they pick to nest are most times poor, and they are less likely to stay on the nest to incubate eggs until they hatch or raise the brood once they do hatch. Game-farm mallards will nest in flowerpots, landscaping, or a pile of leaves on a roof and not stay in the nest until the eggs hatch, unlike a wild mallard that would typically search out a nesting site in a vast area of grasslands where nesting success is higher. A wild hen is also going to teach ducklings how to survive. Because more and more game-farm mallards are breeding with wild mallards and passing on these less-than-ideal traits, mallard duckling production and populations have plummeted in the Great Lakes region and even more so in the Atlantic Flyway. Wild mallards are nearly extinct in the Atlantic Flyway. Yet, genetic inbreeding has not been found in the Mid-Continent Mallard population to any degree.

Luukkonen has been fitting mallards with GPS transmitters to determine their preference for nesting sites and success, mortality, genetic makeup, and migration tendencies. Luukkonen and researchers have placed GPS transmitters on 592 hen mallards across Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana. Of the hens captured, 44% were wild versus 56% domestic. 78% of the ducks were captured from July through September.

Where the ducks are captured has much to do with their genetic makeup. “You go wherever you need to find them,” admitted Michigan Department of Resources researcher Don Avers, who coordinates efforts to capture and band ducks in Michigan. “You find wild birds in different places than domestic birds. Hybrid birds are everywhere!”

Avers said much of their banding effort takes place in southwest Michigan, and banding efforts have increased since 2014. “Drakes far outnumber hens,” said Avers. “Typically, out of 100 ducks, 85 are drakes. What banding has shown us is that domestic hens are bad mothers. They’re poor at selecting nesting sites, poor breeders, and just poor at survival in general.” Avers said upwards of 60% of the ducks they capture are from the Great Lakes Region. The prairies have little effect on mallard numbers in the Great Lakes Region.

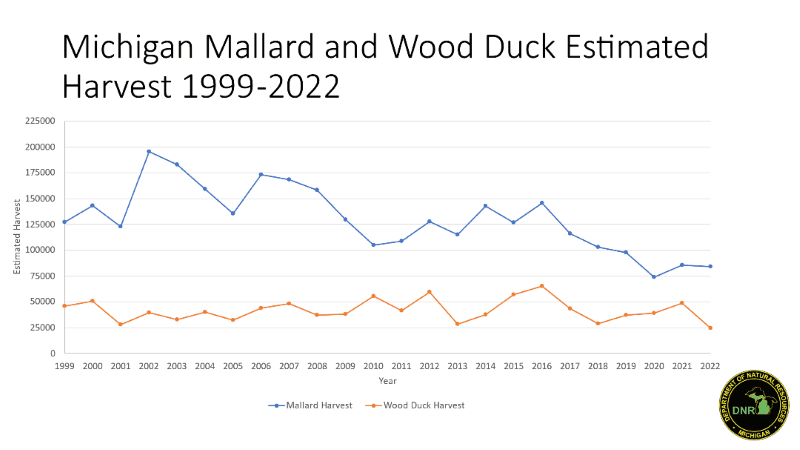

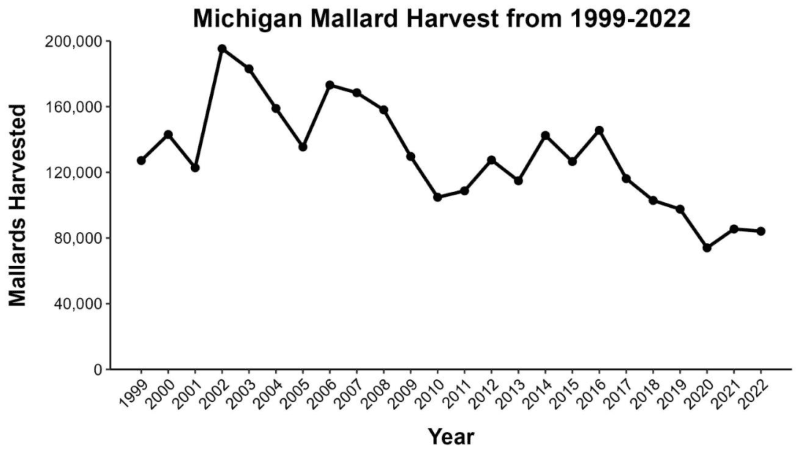

You would think a simple solution would be to shoot fewer mallards. However, researchers have found that hunting mortality makes up a very small percentage of the overall mortality rate. “Hunting mortality accounts for somewhere around 1 to 2% of the total mortality rate,” said Dr. Barb Avers, Waterfowl and Wetland Specialist for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wetland Division. “Mallard harvest from 1999-2019 averaged 48.2% of the overall harvest. Between 2020 and 2023, the percentage of mallards harvested was exactly the same- 48.2%. in the Great Lakes Region.” Avers indicated that the proportion of mallards in Michigan’s total duck harvest has declined over time. Recently, mallards made 41% of the duck harvest.

In Michigan, “the 2023 estimate of total ducks was 136,420, 32 percent below the 2022 estimate and 78 percent below the long-term average. The 2023 estimate for mallards was 82,731, 40 percent below the 2022 estimate, 75 percent below the long-term average, and the lowest estimate ever recorded. Poor survey conditions (e.g., rain and storms delayed the recommended survey start date, and observers reported poorer visibility due to leaf-out conditions on some transects in the Lower Peninsula) and modifying several surveys transects due to interference from airport traffic and wind turbines may account for fewer birds detected.”

Habitat conditions didn’t seem to be an issue in 2023, and conditions were likely similar in other states in the Great Lakes Region. “The 2023 statewide wetland abundance estimate of 461,348 wetlands was six percent below the 2022 estimate and five percent below the long-term average. May 2023 Great Lakes water levels remained above the long-term average and very near May 2022 levels. Based on wetland abundance, Great Lakes water levels, and drought indices, wetland conditions were considered “excellent” for breeding waterfowl statewide except for “good” conditions in portions of southeast Michigan and the central Lower Peninsula. However, very little rainfall throughout June resulted in moderate and severe drought conditions and dry wetland basins throughout much of the Lower Peninsula.” Habitat doesn’t seem to be a major issue in the decline of the GLR mallard population decline.

Avers said only three things can contribute to the mallard decline in the Great Lake Region: habitat, predation, and genetics. Habitat conditions have been quite good in recent years. Predator numbers continue to be high. Competition from expanding mute swans and Canada geese populations is considered a non-factor because mallards, at least wild ones, prefer upland habitats, which leaves us with genetics.

Most hunters go a lifetime without shooting a banded duck. Banded ducks make up a very small percentage of the waterfowl in the wild population. Hunters proudly display them on their call lanyard when they do.

My son, Matt, hunts a Michigan lake where the MDNR has banded mallards in the past. The mallard population there is a classic example of what’s wrong with the mallard population in the Great Lakes Region.

Matt has shot three banded mallards in a single day there- twice. He has shot numerous other banded mallards. He has shot banded mallards whose bands were one number apart, but he shot the ducks five years apart! A hunter is thrilled to shoot one banded duck in his or her lifetime, let alone three in one day.

It’s obvious these ducks don’t go anywhere. They aren’t programmed to. Unlike wild mallards, they live, breed, and die in the same place.